Evaluation

Learn how to develop a ToC-based evaluation

Choose an Appropriate Evaluation Design

Once you’ve identified your questions, you can select an appropriate evaluation design. Evaluation design refers to the overall approach to gathering information or data to answer specific research questions.

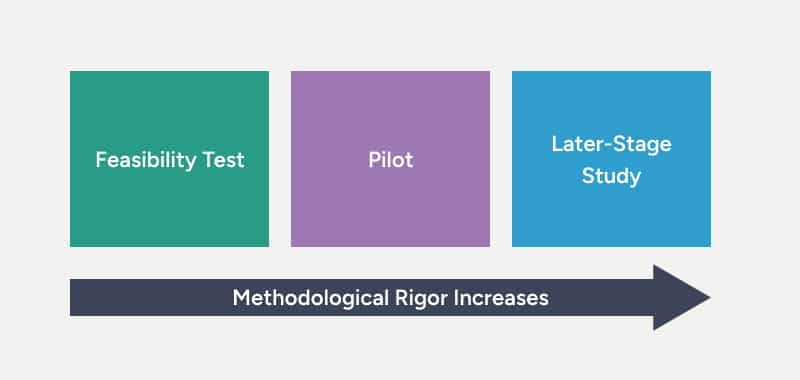

There is a spectrum of research design options—ranging from small-scale feasibility studies (sometimes called road tests) to larger-scale studies that use advanced scientific methodology. Each design option is suited to answer particular research questions.

The appropriate design for a specific project depends on what the project team hopes to learn from a particular implementation and evaluation cycle. Generally, as projects and programs move from small feasibility tests to later stage studies, methodological rigor increases.

In other words, you’ll use more advanced tools and processes that allow you to be more confident in your results. Sample sizes get larger, the number of measurement tools increases, and assessments are often standardized and norm-referenced (designed to compare an individual’s score to a particular population).

In the IDEAS Framework, evaluation is an ongoing, iterative process. The idea is to investigate your ToC one domain at a time, beginning with program strategies and gradually expanding your focus until you’re ready to test the whole theory. Returning to the domino metaphor, we want to see if each domino in the chain is falling the way we expect it to.

Feasibility Study

Begin by asking:

“Are the program strategies feasible and acceptable?”

If you’re designing a program from scratch and implementing it for the first time, you’ll almost always need to begin by establishing feasibility and acceptability. However, suppose you’ve been implementing a program for some time, even without a formal evaluation. In that case, you may have already established feasibility and acceptability simply by demonstrating that the program is possible to implement and that participants feel it’s a good fit. If that’s the case, you might be able to skip over this step, so to speak, and turn your attention to the impact on targets, which we’ll go over in more detail below. On the other hand, for a long-standing program being adapted for a new context or population, you may need to revisit its feasibility and acceptability.

The appropriate evaluation design for answering questions about feasibility and acceptability is typically a feasibility study with a relatively small sample and a simple data collection process.

In this phase, you would collect data on program strategies, including:

- Fidelity data (is the program being implemented as intended?)

- Feedback from participants and program staff (through surveys, focus groups, and interviews)

- Information about recruitment and retention

- Participant demographics (to learn about who you’re serving and whether you’re serving who you intended to serve)

Through fast-cycle iteration, you can use what you learn from a feasibility study to improve the program strategies.

Pilot Study

Once you have evidence to suggest that your strategies are feasible and acceptable, you can take the next step and turn your attention to the impact on targets by asking:

“Is there evidence to suggest that the targets are changing in the anticipated direction?”

The appropriate evaluation design to begin to investigate the impact on targets is usually a pilot study. With a somewhat larger sample and more complex design, pilot studies often gather information from participants before and after they participate in the program. In this phase, you would collect data on program strategies and targets. Note that in each phase, the focus of your evaluation expands to include more domains of your ToC. In a pilot study, in addition to data on targets (your primary focus), you’ll want to gather information on strategies to continue looking at feasibility and acceptability.

In this phase, you would collect data on:

- Program strategies

- Targets

Later Stage Study

Once you’ve established feasibility and acceptability and have evidence to suggest your targets are changing in the expected direction, you’re ready to ask:

“Is there evidence to support our full theory of change?”

In other words, you’ll simultaneously ask:

- Do our strategies continue to be feasible and acceptable?

- Are the targets changing in the anticipated direction?

- Are the outcomes changing in the anticipated direction?

- Do the moderators help explain variability in impact?

The appropriate evaluation design for investigating your entire theory of change is a later-stage study, with a larger sample and more sophisticated study design, often including some kind of control or comparison group. In this phase, you would collect data on all domains of your ToC: strategies, targets, outcomes, and moderators

Common Questions

There may be cases where it does make sense to skip the earlier steps and move right to a later-stage study. But in most cases, investigating your ToC one domain at a time has several benefits. First, later-stage studies are typically costly in terms of time and money. By starting with a relatively small and low-cost feasibility study and working toward more rigorous evaluation, you can ensure that time and money will be well spent on a program that’s more likely to be effective. If you were to skip ahead to a later-stage study, you might be disappointed to find that your outcomes aren’t changing because of problems with feasibility and acceptability, or because your targets aren’t changing (or aren’t changing enough).

Many programs do gather data on outcomes without looking at strategies and targets. One challenge with that approach is that if you don’t see evidence of impact on program outcomes, you won’t be able to know why that’s the case. Was there a problem with feasibility, and the people implementing the program weren’t able to deliver the program as it was intended? Was there an issue with acceptability, and participants tended to skip sessions or drop out of the program early? Maybe the implementation went smoothly, but the strategies just weren’t effective at changing your targets, and that’s where the causal chain broke down. Unless you gather data on strategies and targets, it’s hard to know what went wrong and what you can do to improve the program’s effectiveness.